That Time I Was Expert On The Largest Corrective Advertising Damages Award Case Ever: PODS v. U-Haul

Between 2013 to 2014, I served as an SEO Expert Witness for PODS Enterprises, Inc., as they sued U-Haul International, Inc. It was a fascinating case and, in many ways, astonishing, not least of all because PODS was awarded the largest corrective advertising damages award in history.

The back story, as I understood it, was that PODS was something of a major disruptor in the Moving & Storage industry.

When people are moving, they need transportation for the items being moved, and then they need a lot of various equipment around moving. Sometimes, people also need temporary storage space for items they are moving. U-Haul started out as a family-run business many years ago (founded by Leonard Samuel Shoen and his wife, Anna Mary Shoen), and kept expanding and adding locations until they were the biggest kid on the block. As the biggest company in the business, stretching back many decades and still led by members of the founding family, the company also had a lot of egos and a lot of hubris. (To get some perspective, there were decades of family infighting, lawsuits, and even allegations of murder in the Shoen clan, so the moving company dynasty was not passed down easily, and you get the impression that the folks at the top can be pretty cut-throat and nasty. See: https://www.forbes.com/sites/luisakroll/2016/02/10/inside-u-hauls-rollercoaster-ride-from-nastiest-family-feud-to-market-dominance/)

Anyway, in 1998, the PODS company was founded by Peter Warhurst who was seeking to expand his family’s storage business. He invented PODS containers and a lift system that enabled operators to easily transport the containers from place to place. Different from the classic moving truck system, one could have a PODS container dropped off in a driveway or street, and the box-like container could then be filled up. These containers could be used like a storage shed on a property for an unspecified length of time while paying ongoing rent on the container, or, after being loaded up, the container could be picked up once more and taken to another place where it could be dropped off and unloaded. The concept was a major disruptor in the moving and storage business because it increased flexibility for customers and combined elements of moving and storage in a compelling way.

The story goes that U-Haul recognized the value of this newly emergent method and approached the PODS company to discuss its potential acquisition of it. It could be said that U-Haul had a bit of a history in attempting to monopolize the market by acquiring or even aggressively attacking agile startups. It acquired collegeboxes.com in 2010, a moving company that grew out of a student project at Duke University, and it had sued HireAHelper’s founders around 2005 in a suit that was described as a large company using costly litigation to attempt to hamstring or shut down what it perceived as a competitive threat (see descriptions here and here).

Very obviously, PODS was an industry disruptor that presented a significant competitive threat to U-Haul; although I would hesitate to describe it as an “existential threat” — but it would not be surprising if U-Haul executives could have perceived it as an existential threat. Regardless, PODS clearly could and was a rising competitor that was starting to cut into U-Haul profits, and if PODS’ rate of growth continued, it could cut into U-Haul profits significantly.

Reportedly, U-Haul had approached PODS Enterprises with the idea of potentially acquiring the company. After six months or so, the talks came to nothing, and PODS was acquired by another company.

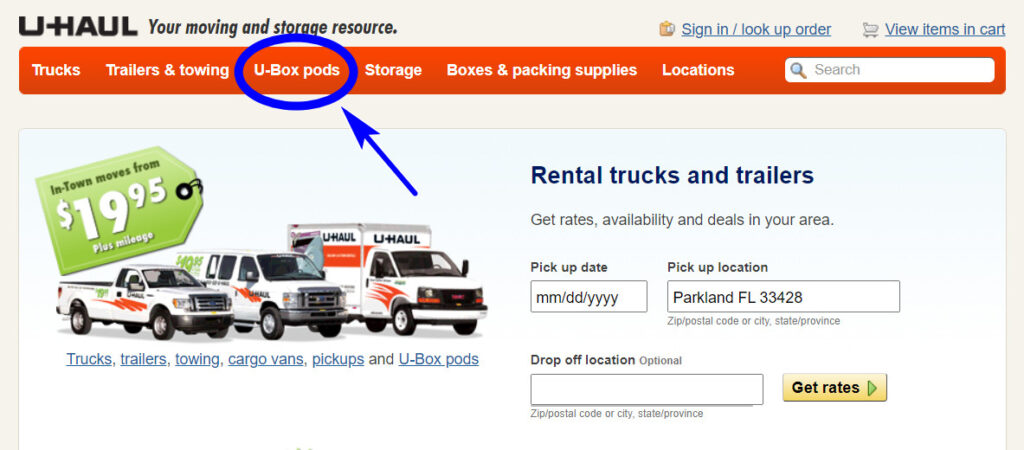

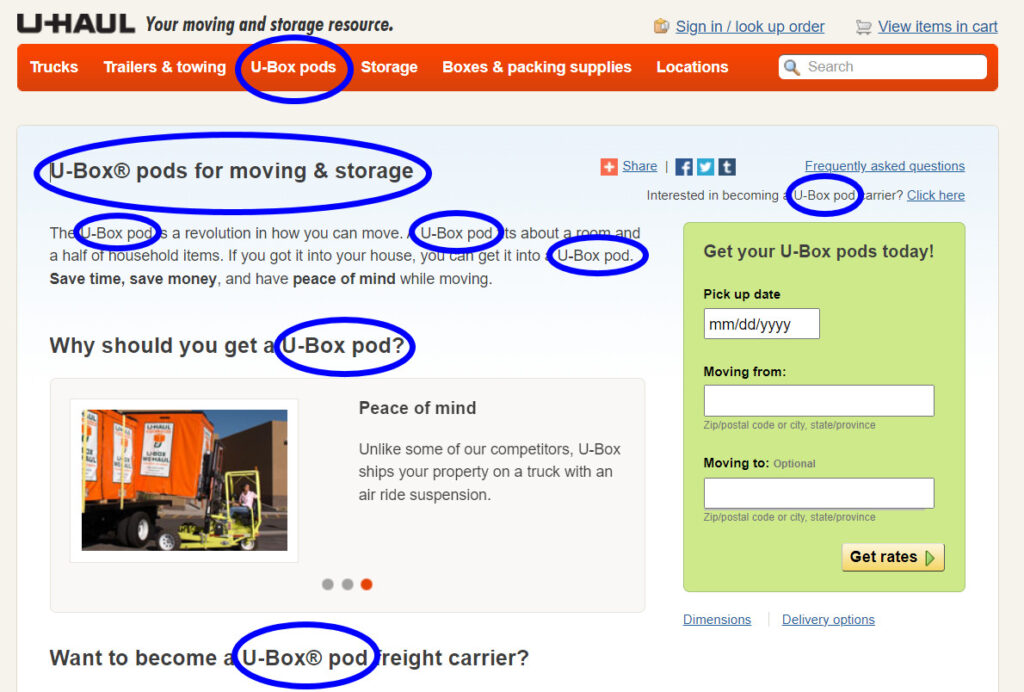

U-Haul apparently determined it would simply create its own competitive portable storage container unit system, and dubbed it “U-Box”. But, PODS’ product had already gained a foothold, and the “PODS” name had seemed to gain an advantage of being unique and distinctive while simultaneously describing aspects of their moving/storage system. One can speculate that either the name was just too perfect for the moving/storage process or U-Haul thought they could deliver a harmful blow to the competitor by cancelling their mark. Either way, instead of merely launching a competitive product and then promoting their own “U-Box” brand name for it, U-Haul combined the U-Box name with PODS, frequently in all lowercase, or sometimes with just the initial letter capitalized. U-Haul did this in a massively visible manner, launching a “U-Box pods” section on their uhaul.com website, with a link in the header, and also footer links, links within the homepage, and interlinked throughout content elsewhere and in external web promotions.

I was approached and hired by council to serve as an SEO Expert Witness, as they suspected or were told by marketers within the PODS company that the incorporation of the PODS mark throughout the U-Haul website would enable uhaul.com pages to appear more prominently in search results for “PODS” searches. I was tasked with assessing if the pages had been optimized to rank well for PODS searches, if this impacted their rankings, whether this increased consumer exposure to the infringing mark use, and, if so, how many times consumers could have seen the mark.

The SEO Audit / Analysis I conducted of the uhaul.com website was easy — almost brutally easy. The incorporation of the PODS mark was so very overt, and the SEO professionals working for U-Haul actually did an amazing job of optimizing the website for this keyword, albeit that they had apparently been instructed to use their skills in a conspiracy to illegally and unfairly cancel the trademark of a smaller competitor. (I’m not criticizing those who conducted the optimization work — SEO pros are not necessarily expected to be knowledgeable about IP law when working at the behest of a huge company — the responsibility for this falls on the shoulders of executives and corporate counsel that directed, oversaw, and approved of this SEO effort.)

Anyway, the SEO analysis was brutally easy because the PODS mark had been incorporated throughout the website’s code in all the classic places: titles, meta descriptions, headings (<h2> tag text), visible text, image alt text, etc. Examples:

As anyone with an SEO background can see, establishing that U-Haul had conducted SEO with the PODS word mark was very straightforward. So much so that it seemed clear from context, additional SEO elements, and the on-page elements that U-Haul had very intentionally conducted SEO to enable the site’s pages to appear prominently for search queries involving moving and storage that contained “PODS”. This was so extremely clear that this part of the case was not in contention — U-Haul’s expert essentially agreed to my analysis on these points. (I did further analysis as well — U-Haul had performed some external SEO and Local SEO with directory listings for their thousands of locations all over North America. These items further widened the exposure/distribution of the infringing mark, but these elements were just a small portion compared to the exposure in search engines’ regular search results.

However, the more significant work that I did on the case was to help quantify the numbers of times that the PODS mark was misused on the U-Haul website, and how many times it would have been seen by consumers, i.e. “misimpressions”.

“Misimpressions” is an interesting concept.

If you are familiar with the internet marketing industry, you may know that “impressions” are one of the dominant advertising measurements for many types of online ads — an impression is when a discreet ad unit has been displayed to an internet user. In the earlier days of the internet, ads were often sold on an impression basis, such as “CPM”, which stands for “cost per thousand” (as the old Latin word for thousand is “mille”). Slightly later, ads were sold on a “cost per click” basis, which became very compelling as it allowed for more direct measurement for eliciting desired activity. (Even more effective is “pay-per-sale” or “pay-per-conversion activity”.)

The degree or scale at which a trademark infringement is witness by consumers in the marketplace is one means of measuring how much impact an act of infringement has had. If only one or two people have seen an infringement out of tens of thousands, then the degree of harm might be considered pretty light or negligible, for instance. Thus, the term “misimpressions” is a metric for measuring how many times a infringement is witnessed by consumers.

Technically speaking, it is my understanding that each discreet instance of infringement that is witnessed may be used to factor into a misimpressions measurement in a Lanham Act trademark infringement case. Because of this, if a trademark is used multiple times on a single webpage, then technically each of those uses could be counted, similar to how ad impressions can be counted (if a banner ad is shown at the top of a webpage, and also at the bottom, then two separate ad impressions could be counted — albeit some ad accounting systems also take into account if a single, unique user has seen the same ad multiple times within a short timespan the system may only count one impression).

As you can see from the example screengrab I showed above from the uhaul.com website, “PODS” was used multiple times visibly on U-Haul’s webpages, and technically one could count a single webpage visit as representing around 11 or 12 misimpressions. While that accounting might sound excessive, consider that the law might look at this somewhat like each use of the mark on the webpage is a separate promotional instance, much like how each use of the mark could be considered to be a separate ad unit. And, each repetition of the PODS mark in this case, used in lowercase as though it is a generic term, creates a further-developing unconscious sense on the part of unaware consumers that “pods” must be a generic description that could apply to any similar product provided by any company in the moving and storage industry. The repetition makes it seem more like an expectable, everyday generic word use.

Even had U-Haul only mentioned “PODS” visibily once per each webpage, the scale was very large. As I recall, their website had something on the order of almost 200,000 webpages at that time, many of them targeting their 20,000+ locations in the US alone. Considering that “U-Box pods” was a link in their site-wide header, the scale of the infringement was already very high — anyone visiting any of the site’s pages would’ve been exposed to the mark.

But, U-Haul’s optimization efforts actually widened the scale further, because the U-Box subsection pages had become indexed, and those pages’ titles and meta descriptions appeared in the search results for whenever people were searching for PODS throughout the country.

I was presented with a big difficulty that comes up frequently in internet infringement cases: how to find out how many people could have conducted searches where the U-Haul U-Box pages would have appeared in the first page of search results? We did not initially have access to uhaul.com analytics when I wrote my first report, so we needed another source — this was something the attorneys asked me if I had any ideas.

I fortunately had read articles for some years that cited data from Hitwise, which was a brilliant research analytics company that collected terabytes of data from internet users. They purchased this data from ISPs, and combined it together in many useful ways for marketers. They had data on how many people conducted searches for things like “moving pods” and “storage pods”, and a few other queries that I had determined were frequently used by consumers when trying to locate these types of products/services. Purchasing access to their reporting system for just a brief, one-month period to perform the analysis cost thousands and thousands of dollars. Even more challenging, Hitwise created their own unique measurement unit to provide comparative numbers — their tools were used more for competitive intelligence and market research. But, as I needed raw, actual numbers, one of their engineers provided me with equations to reverse-engineer their data to provide us with the raw numbers of visits and unique visitors. This gave us numbers for: how many people searched for “pods” queries in Google, Yahoo, and Microsoft Live search where the search results also displayed pages from the uhaul.com website. Further, it also provided numbers for how many people then clicked through to uhaul.com pages after conducting such searches.

Thus, I could add up the numbers of misimpressions from consumers who would have seen the “PODS” mark in U-Haul’s website listings in search engines, plus the numbers of visits U-Haul received from those searches, times the numbers of times the “PODS” word was found on those uhaul.com pages.

This process resulted in accounting for many millions of misimpressions!

I noted in my expert report how these numbers were further conservative because Hitwise could only measure a subset of all internet traffic — much usage does not get captured by such a system because many businesses, schools, and smaller ISPs do not provide internet usage data logs to such companies.

The misimpression exposure was actually wider than just the online component because U-Haul had also used the mark inappropriately in other, offline communications, branding, and advertising. But, the online component likely had the largest visibility, and was also the most compelling because the internet analytics made it measurable and provable how many people would have seen the misuse.

There were a number of conversations among those of us who worked on the case. Because of the measurability, and because it makes sense to try to make up for the misuse in the same channel where consumers would have seen the infringed mark, it was determined that a corrective advertising campaign would be one of the best basis for damages assessment in court. There are a few models for damages under the Lanham Act, and those models can be combined when assessing total damages. There were also to be potential lost revenue, disgorgement of illegally obtained revenue, and potential punitive damages.

We first used a method for estimating corrective advertising costs by estimating the potential cost of conducting online advertising based upon going rates for PPC ads and multiplying that over the total misimpressions. Using the raw numbers I had obtained for misimpressions, the total resultant number in dollars was astonishingly high — probably too high by the estimation of the attorneys at Stroock & Stroock & Lavan LLP.

The marketing expert witness, Dr. Russ Winer, came up with an equation that reduced the total number through eliminating some or all of the multiple misimpressions-per-page counts, and instead counting one misimpression for the listings clicked in search results, and one misimpression on the landing page at uhaul.com. By the time of the trial, I believe we had been provided some of uhaul.com’s own website analytics numbers which we used instead of the Hitwise undercounts, too. He also reduced the amount of counted impressions by another factor as well — perhaps out of purely making a representation of providing an ultra-conservative count to the court, or perhaps out of estimating that the jury might consider one misimpression per unique visitor fairer than counting multiple misimpressions seen by the same person.

The trial was nothing short of dramatic, and it was my first time to witness the inner workings of a legal team of litigators in action. It was highly educational for me, and worth solid gold in terms of preparing me for a side career as an expert witness.

U-Haul really played hardball. I heard they rented out an entire floor of a hotel for their war-room for the trial. They seemed to have around 8 attorneys to PODS’ 3-4 attorneys. There were 4 expert witnesses on PODS’s side (an SEO/Analytics expert witness, a marketing expert witness, a forensic accountant expert witness, and a market surveying expert witness). U-Haul apparently sought to counter us with around 10 expert witnesses on their side, including one retired 4-star general.

U-Haul really went after the survey expert — three of their expert witnesses were brought in to criticize and try to tear down his testimony — about two of those experts were past students of the elderly PODS survey expert!

You might well be wondering who they brought in to critique my expert report — it was Jonathan Hochman, and he did a very good job in representing his clients and also maintaining superb professionalism. I do not like admitting making any mistakes or being wrong, but I will say that he did very well in criticizing the weakest part of my initial expert report, and if I were forced to answer under oath, I would likely agree with the most substantive parts of his criticism in retrospect on that case. But, my client ultimately prevailed because they had such a strong case and because U-Haul had conducted such a blatant and ugly effort to genericize their trademark. As I said earlier, the SEO was so textbook and clear that no one expert in the SEO field could reasonably contest what I said about their efforts to show up organically for “PODS” search terms. Hochman focused his criticism on the trustworthiness of the analytics data, as I recall, which is open to some degree of criticism as any third-party competitive statistic service will be, and his most substantive criticism was against my estimates on potential PPC ad costs, which I believe was deserved in that case.

I will not go into all the elements of the trial, which took a number of days to conduct, but there were a number of dramatic moments throughout, and I managed to do a good job when it came my time to take the stand — some of those tales at the trial perhaps deserve their own article. But, I will say there were a number of instances where U-Haul was shown to be aggressive, even predatory, and outright deceptive, and the collection of pieces of evidence and testimony caused the jury to find in favor of PODS.

This is how PODS was awarded $62 million in damages in the lawsuit against U-Haul.

What came afterward was anticlimactical. Unsurprisingly, U-Haul appealed the decision and the award, stretching out the litigation further afterward. In 2016, PODS agreed to settle the case with U-Haul in order to put an end to the litigation, accepting $41.4 million in damages instead of the original $62 million. Sadly, once PODS’ franchise owners saw the corrective advertising award, they felt that they deserved a portion of that award as well, and they sued PODS Enterprises in a class action to get what they perceived to be their share of the pie. I was later contacted by an expert witness working on that franchisee lawsuit, who asked me questions related to statistics in the original case. I lost track of the outcome on that case.

It was fascinating to have worked on this landmark case because it seemed to wake up IP attorneys as to the potential for collecting damages based on corrective advertising. My understanding is that prior to the PODS v. U-Haul case, trademark infringement lawsuits could be expected to have relatively low overall awards coupled with attaining court orders directing infringers to desist in conducting infringing activities.

There was a really unique set of circumstances that paved the way for a case like PODS v. U-Haul to happen. You had a major company that intentionally infringed in an effort to cancel a company’s valuable trademark. The target of this effort at genericization decided to go to war to stop it. You had a talented legal team that explored all options to punish the infringer. You had skilled experts to clench the deal on each of their own respective pieces of expertise. You had a jury that was offended at the bull-dozing tactics of the infringer. You had a scale of misimpressions that was gigantic and a company with income big enough to pay a large penalty. You also had access to internet usage statistics that every day are becoming harder to access (Hitwise went defunct in 2020 or defacto even earlier).

Can another corrective advertising damages award ever hit that size? I think there remains the potential to do so.