Epic Win vs. Google in Australian Case

I was recently hired by an individual in Australia that sued Google to compel them to be more responsible for her online reputation as reflected in the search results. This was a real-life David-versus-Goliath fight where a single individual became unhappy after Google did not adequately remove listings from their name search results after the complainant had submitted a formal removal request. Thus it came to be that Dr. Janice Duffy filed a lawsuit in Australia.

Dr. Duffy ultimately prevailed in her case with my assistance as a testifying expert witness.

The case was fairly unusual for a number of reasons:

- Dr. Duffy initially sued Google some years ago and prevailed in that lawsuit. But Google’s response afterward was inadequate, and thus Dr. Duffy determined to sue them again to ask the court to compel them to provide relief.

- Google partially responded by removing one of the two requested URLs from search results but neglectfully left the other present. Thus, their primary exposure in the case.

- Further, the damaging content was published on Ripoff Report, which has a longstanding, infamous reputation for hosting defamatory content, and Ripoff Report made site changes that caused materials that had been removed from Google’s search results to become republished anew. This made Google potentially further liable as it had already become responsible for the negative content’s presence in its search results.

- After expending large amounts of money in her initial case, Dr. Duffy appeared in court this time pro se; that is, she represented herself without having an attorney present.

- Google attempted to argue that it should not be held liable for defamatory search results which were authored and published by third parties, which is its position in the United States and other jurisdictions where they can persuade lawmakers that it should not be held liable. However, under Australian law, when a publisher is duly notified that some material is defamatory, they have a few days in which to remove it, or else the publisher becomes liable for the content themselves. By failing to remove the content, Google had become liable for it, placing the onus on the company to ensure it was removed.

- The case provides a clear illustration for those in the United States as to why Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act is in need of some modification because there are a lot of instances where false and defamatory material is made too prominent in search results and search engines provide the best or only real recourse to removal and relief for impacted persons.

I had qualms about serving as an expert witness for a client that is suing Google for a number of reasons. For one, my agency, Argent Media, performs search marketing and reputation management on behalf of individuals and companies, and Google could very easily harm my business. While I have long known many people in Google that would not conduct reprisals merely because someone criticized the company, it is within the realm of possibilities. It is no easy matter to consider working against a platform that one’s business is reliant upon.

Personnel within Google have helped me numerous times in resolving issues on behalf of clients. I had to consider whether these friends and colleagues would be offended at my involvement in a lawsuit against their company.

Further, there are many within the search marketing industry as well as without who believe that Google should not be held liable for what is published on individual websites, and if this case prevails, it tends to strike a blow at that philosophy. I had to seriously consider whether my involvement with this case would damage my own reputation if valued colleagues were to think that I was harming the internet itself.

I also had a real concern about whether my involvement would help the plaintiff or if I would not be able to provide anything that would support her case. It should go without saying for all ethically-minded experts, but I would not lie for a client, and I only wish to be accurate, knowledgible, reasonable, and truthful in providing expert witness services. (Some experts seem to view professional witness work as though they are hired guns, and they will support even bizarre interpretations of facts and evidence in return for pay. Under Australia’s laws and other former British colonies, expert witnesses are formally considered agents working on behalf of the court rather than directly on behalf of either party to a case.) I was afraid that there might not be much that I could add to Dr. Duffy’s case, and if not, there would be no point in accepting money for the work.

However, after careful consideration, I accepted the case.

While there is certainly a larger degree of responsibility that ought to be placed upon authors of defamation and the websites that may host it before Google is even in the picture, the reality is that there may often be times when defamation authors may be unidentifiable, and the hosting websites may be out of legal reach or otherwise cannot be compelled to remove the content. Google is simply in the best position to provide relief to those who have had their reputations unfairly harmed on the internet.

Also, I had previously represented another individual who sued Google in the UK for similar reasons around seven years ago, and Google had elected to settle the case by about midnight on the eve of the case going to trial. While that outcome was great for my client in the UK, it was dissatisfying because it did not make any sort of definitive determination about legal responsibility for online defamation — so that case mainly helped only one individual rather than benefitting all online defamation victims. Thus, I hoped that the present case would potentially illustrate how individuals ought to have greater relief available to them in terms of search engines’ reasonable responsibility.

Another reason why I chose to work the case was that I believe that many Googlers are themselves highly ethical people and are not blindly loyal to the corporation. Thus, if I have reasonable bases for the opinions I rendered in the case, I believe my friends and acquaintances within the company will still respect me and might even agree with my assessments.

Once I delved into the case, my qualms about working on it disappeared. I was provided expert reports from two of Google’s engineers who were asked to provide technical perspectives on vital issues in the case, and I quickly saw a number of instances where the engineers were either myopically incapable of seeing how the company’s handling of these issues can cause frustration for individuals. Google’s attorneys and the two engineers collectively could be described as being oblivious to their legal obligations under Australian law and how their procedures for handling removals were unnecessarily failing at satisfying those obligations.

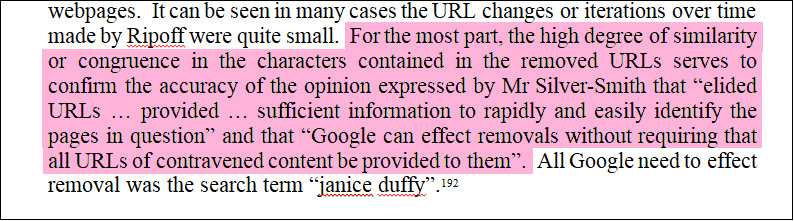

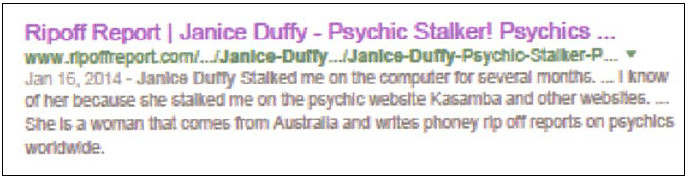

The primary point where my expert report was key to supporting the complainant’s case was where Google’s engineers had tried to rationalize and excuse their failure to remove one of the links from search results. Dr. Duffy was not an internet technology expert when she submitted a removal request to Google. Being inexperienced at this, instead of submitting the URLs of the pages associated with the two listings she wanted removed, Dr. Duffy had a printout of the results page, and she marked the two listings needing removal.

However, Google’s standard practice has been to require that defamatory stuff needing to be removed needed to be submitted to them as a list of full URLs. Dr. Duffy’s printouts only showed the listing’s text, and one could only see abbreviated URLs or “elided URLs,” as the engineers referred to them. An “elided URL” is a shortened version of a page’s URL since Google limits how many characters will be displayed from a URL with the page listings. In order to standardize display, longer URLs will get lopped off for in the search results, and the ending will show an ellipsis ( . . . ). Example:

https://trademarkinfringement.expert/what-is-trademark…

Google’s two engineers each provided a report in the case (the case stretched on for some years, so the first engineer had left the company by the time it was finally coming to court, so the second engineer supported the claims of the first one’s report, and also updated some out-of-date information and expanded further). The second engineer’s report, in part, had claimed that Google must be supplied entire URLs in order for them to effectively remove content and also supported this claim further by expostulating upon how Google contains and processes over a trillion URLs, making it too hard to locate pieces of content for removal without the specific URLs.

Whenever I tell this story, I must point out how utterly facile and ludicrous these positions were for Google’s engineer to have claimed!

I debunked this wrong statement with a few facts and provided the court with a method for independently establishing that the engineer’s statements were highly misleading. Here are the points I hammered home:

- Google is the most powerful search engine on the face of the earth, having evolved over more than 20 years and incorporating multiple engineering teams and multiple methods — including artificial intelligence processing — in order to contain trillions of URLs and provide answers to search queries in mere seconds.

- Expecting inexperienced users to perfectly provide Google with URLs for removals is unreasonable and often fraught with difficulties. This had been a central issue in the Hegglin v. Google case I had served in years earlier in the United Kingdom and remained a fairly ridiculous stance for them to maintain almost a decade later. In the earlier case, there were instances where requested removals were submitted for the index pages of forums or blogs, and once Google’s removal team rapidly checked them (weeks after they were submitted in some cases), those types of sites have had so many subsequent entries added that the original defamatory content was moved off of the first pages onto second pages, or continuous-scrolling pages didn’t initially reflect the defamatory content, and so items would not be seen to substantiate removal requests unless Google’s personnel scrolled further and further. And similar to Duffy’s case, there are various errors that can commonly occur when inexperienced users attempt to provide URLs for removal and where Google could do more to figure out the actual URLs for removal.

- One thing Google is very good at is finding URLs that you are looking for. The screengrabs that Dr. Duffy had provided to establish what she wanted removed were sufficient in of themselves for Google’s personnel to have removed them.

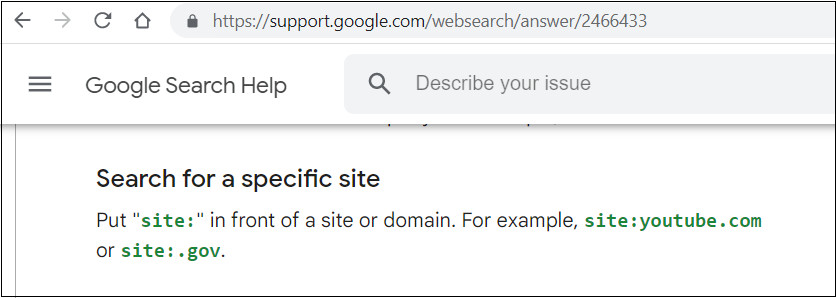

- I pointed out that Google openly provides search refinement commands and advanced search operators so that any user could conduct a search among ONLY the webpages of a particular website by putting “site:” before a domain name to search:

- By using a site: search for the ripoffreport.com website, any of Google’s removal personnel could have used the screengrabs of listings Dr. Duffy had provided to locate the specific page URLs for which she was requesting removal. The “site:ripoffreport.com” query reduced down the field of all the trillions of pages on the internet to less than 100,000. Combining additional query parameters like “janice duffy” and “inurl:Janice-Duffy-Psychic-Stalker” results in Google zeroing-in on the specific page in an instant. Thus, the judge could clearly see that trained Google personnel, and particularly the engineers claiming that finding Ripoff Report URLs about Dr. Duffy were too difficult because they’d be seeking a needle in a haystack of trillions of webpages — that assertion was clearly false on the face of it. The judge himself was able to conduct the search in order to easily locate the URLs in question.

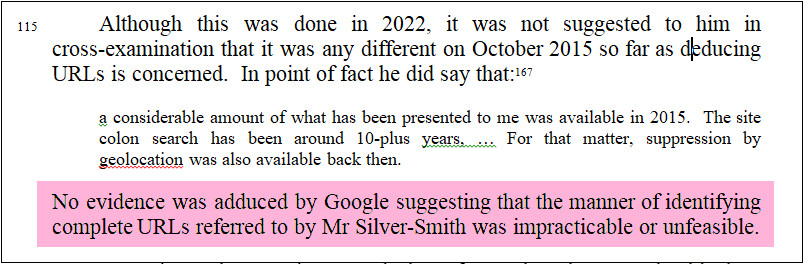

- There were additional issues involving whether Google ought to be required to remove content in other jurisdictions when asked to remove something in a particular country. This seemed to boil down to a legal determination rather than a technical one, and also, the judge was influenced by Google’s claims that Duffy’s search results in the US version of Google were shown to only a minor number of people. (In my earlier UK case, I had sought to debunk Google’s claim that suppression by geolocation was technically infeasible. Google changed how they handled suppression of removed content within a year or two of that earlier case, suggesting that they knew they were in an indefensible position on that topic after my report in the Hegglin case.)

- Google has also argued that they cannot suppress content based on the substance of the content itself, rather than by specific URLs. This is technically untrue because they do this literally all the time now, such as when detecting copyright-infringing material automatically in YouTube videos and suspending it. Implementation of automated detection and suppression for removed defamatory content would assist victims more as they would not be required to monitor for new emergences of the same defamatory content over time, and they would not be required to send repeated requests to remove the same materials over and over again. (This sort of solution would have kept Ripoff Report from being able to subvert Google’s removal process, for instance.) I pointed out that Google personnel in the past year had just announced that they would implement a “special victims” designation for some individuals who were subject to repeated, ongoing attacks, and they would automatically detect and suppress defamatory materials for them without necessitating victims conduct ongoing monitoring and submission requests for removals. It’s very hard for the company to deny what their own personnel have announced they can and would do!

- I also pointed out that Google had become aware of Ripoff Report’s apparent subversion of their removal process, and knowing this, Google could and should have automatically countered Ripoff Report’s repeated reintroductions of previously removed defamatory materials. While in the U.S. the Section 230 law made Google legally not responsible for doing this, under Australian laws, Google already had a duty to ensure the removal of materials as requested by defamation victims, and thus they also had a higher duty to protect those victims from further predictable harmful acts on the part of Ripoff Report’s operators. (In my 2017 article that first revealed Ripoff Report making site changes that caused removed URLs to be reintroduced in Google search results, I strongly suggested Google penalize the site, such as removing it entirely from the index, by referring to Ripoff Report’s actions as “black-hat.” I had also advocated for Google to develop a different defamation removal method that would not be URL-dependent.

As a result, the Honourable Auxiliary Justice Tilmouth of Australia’s Supreme Court of South Australia found in favor of Dr. Duffy on a number of key points. The justice cited my report and court testimony a number of times in the written judgment and further pointed out that Google said nothing to counter some of my key findings.

The judgment was issued in February, 2023, and it sets a clear precedent that if defamatory content appears in search results in Australia (it must be defamatory in of itself, as an earlier case established that if the listings are neutral but merely link to defamatory content, the search engine may not be held responsible), the search engines such as Google have a duty to remove the content within a reasonable period of time. Because of this reasonable requirement to assist individuals that may be harmed by search results appearing for their name, Google and other search engines cannot merely fall back upon a pedantic requirement that places onus on victims to perfectly submit URLs for removals when Google could easily locate the material, and Google should take reasonable measures to keep removed content from being repeatedly reintroduced.

Further legal analysis and commentary is provided in the following articles:

- “Case Law, Australia: Duffy v Google Inc (No 2), Damages of Aus$100,000 awarded against Google for publication of defamatory snippets and hyperlinks“

- Search engine liability for defamation: Duffy v Google(2)

Additional coverage:

- The Sydney Morning Herald: “The Australian woman who took on Google twice – and won both times“

- Australian Computer Society: “SA Woman Wins Second Google Defamation Lawsuit“

- ABC News: “Adelaide woman wins second defamation case against Google over search results“