Is Initial Interest Confusion A Viable Strategy In Trademark Infringement Cases?

I recently wrote an article on how Initial Interest Confusion (“IIC”) came up in a recent trademark infringement case (see: “Initial Interest Confusion rears its ugly head once more in trademark infringement case“). Quite a number of prominent legal wags are withering in their scorn towards the legal theory of Initial Interest Confusion. But, from my perspective, it’s easy to see where the basis of the legal premise originated: it is a form of bait-and-switch. Consumers may be shown one thing when they’re seeking a particular brand of a product or service, but by the time they follow the process through the only option is to buy a brand that is different from what they specifically sought at the inception of their purchase journey.

Do not get me wrong — I am somewhat aligned with some portion of the criticism against the concept of IIC. The primary criticisms seem to be that: (1) the definition is hazy; (2) the criteria for establishing it is insufficiently imprecise; and (3) in cases where it has been applied, it has seemed to be too heavily centered upon an assumption that consumers are too stupid to tell that what they’re finally buying may be a different brand from what they initially sought. I agree that there is some degree of basis for these criticisms.

So, the question is whether Initial Interest Confusion should be considered a viable strategy in trademark infringement cases? Read on, and I think you may find my strategic assessment valid.

However, I cannot completely escape the foundational premise, either, that a bait-and-switch scenario is a cheat that may be constructed in such a way as to unfairly and improperly dupe a consumer. The entire concept of trademark infringement is based on this to a large degree. One cannot paste the trademarks of one’s competitors on products to trick consumers into thinking they’re buying something from the actual owner of a mark when they really are not.

Initial Interest Confusion has been cited in situations in internet usage where consumers search for something with a trademark name only to be presented with search results containing all or some items that are not provided by the mark owner. Some instances seem (perhaps by tradition and established precedent) to be naturally allowable for this — such as when users may search for a product in a search engine, only to be presented by some search results for similar competitors, including paid ads that were specifically targeted based on brand name keywords. Internet users also seem to be accustomed to the often-fuzzy imprecision of search engines’ results, and the variety of things that can appear there — and they are adapted to using those results as part of a process where they iteratively zero-in on what they ultimately want to find and buy. By dint of habit, these users are far less likely to be duped by searching for one brand, only to be presented with a mix of content that may include the brand as well as the brand’s competitors, and then they ultimately decide what they’ll buy.

Some of the critics of Initial Interest Confusion have compared this process to being offered Pepsi when asking for Coca-Cola in a restaurant — that offer of a similarly equivalent option is not confusing, and it should not be considered that the restaurant committed trademark infringement by doing so. (This amusingly reminds me of the Coke-vs-Pepsi taste test, also known as the “Pepsi Challenge”, where people were persuaded to do blindfolded comparisons of the taste of Coca-Cola and Pepsi soft drinks, and once the actual brands were unveiled, they expressed surprise about which-was-which and discovered they’d be just as happy with the flavor of Pepsi as the more-popular and better-known brand, Coke.) However, being silently presented with search results versus being informed you buy a different cola to drink seems like a world of difference to me. In one instance, you’ve asked for something and have been explicitly informed that what you requested is not available, but you may buy a similar competitor. In the other instance, you’ve asked for something and the disclosure that what you’re being offered may not be nearly as overt nor obvious to you. For anyone that has seen the actual Coke vs. Pepsi issue played out many times in many restaurants, you’ll know that many people are quite dissatisfied with being offered something other than what they really want.

In the Multi Time Machine versus Amazon case a few years ago that involved Initial Interest Confusion, Amazon was ultimately found to be not infringing on MTM’s watches because their search results were labelled to indicate that they were “related”, the individual product listings were clearly labelled as brands different from MTM, and consumers informed enough to search for Multi Time Machine “special ops” watches would likely be knowledgeable enough to see that the prices of the related items were lower than typical.

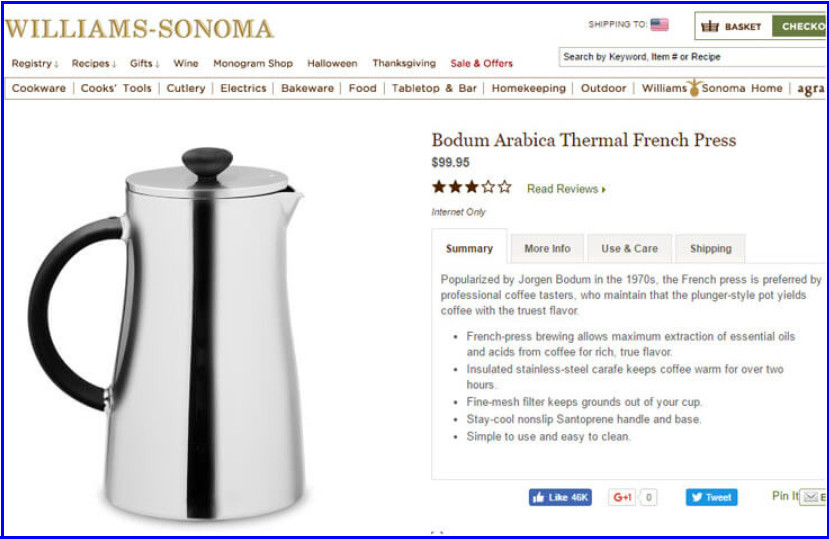

The more recent Bodum vs. Williams-Sonoma case seemed potentially hazier to me for a few reasons. On the scale between general search engine results where people expect to be presented with a variety of closely-matching to fuzzier-matching results, and the opposite end of the scale where a competitor has illegally slapped their competitor’s logo on a product to fool consumers, the Bodum/Williams-Sonoma case seemed further towards infringing than not-infringing to me for a few reasons.

Williams-Sonoma had apparently been selling Bodum’s French press coffee makers for quite a number of years prior to the companies “breaking-up” as vendor-retailer partners. Williams-Sonoma sells somewhat high-end merchandise, has a large brick-and-mortar as well as online footprint, and has many devoted repeat customers. They also sell a mixture of others’ brand products along with items they’ve branded as uniquely Williams-Sonoma. As such, I think that quite a few of the products they carry may be things that their devoted customers have never seen offered elsewhere. I also think that the combination of others’ branded products along with their own WIlliams-Sonoma products have likely resulted in a degree of consumer confusion about brand identity of the items they sell. Consumers often have a degree of confusion between the manufacturer brand of an item and the brand of a store where they buy such items. In fact, many large department stores have contributed to this confusion because they will develop brand names that differ from their stores’ names — but, those specialized brands may only be bought at their stores. (This is highly common practice where many producers and manufacturers will sell products under their own brand names, and offer deals with their distributors to also sell “white-labelled” items so that the distributors may affix their own branding to products as well.)

So, many customers likely only ever encountered Bodum brand French presses in Williams-Sonoma stores, and were accustomed to finding them through Williams-Sonoma for years. Until, abruptly, the two companies parted ways. Afterwards, Williams-Sonoma contracted with some manufacturer to produce French presses that looked a little similar, only they were Williams-Sonoma branded items. They created listings in their online catalog that looked quite similar in styling and presentation to the original Bodum products. Their online catalog search results were not as clearly labelled to signal that they weren’t actual Bodum items (unlike the Amazon case, their search results weren’t labelled as “related”), and they allowed their catalog search results for “bodum french press” to be indexed in Google as well.

Due to the close association between Bodum and WIlliams-Sonoma for some years, I think that consumers likely conflated the two brands considerably in their minds. The companies’ prior relationship bordered perhaps on a cobranding scenario. Due to that past, close relationship, and the newer indistinctness of the search results and presentation, I think there likely was a high chance of confusion of trademarks in customer’s minds.

What I find interesting is that this recent case seems to demonstrate that there may be a scale between acceptable use of branded search results containing official and competitor trademarked results, and a point at which providing such results may go over the line into being too confusing and posing an actual bait-and-switch scenario that should be considered to be a form of trademark infringement.

The determination might be: would a preponderance of searchers in the situation be confused as to the provenance of the products they are presented-with? If reasonably the answer is “yes”, then infringement has occurred.

Considering how IIC is a popular target for scorn among other legal commentators, Bodum may have been wise to avoid using that terminology when filing their complaint against Williams-Sonoma. Perhaps it would be best to just simply call this “trademark infringement” rather than incurring controversy by using the legal jargon.

However you want to call it, case law around this still appears to be somewhat fluid, and it looks like it is still a fairly viable strategy upon which to base a claim of infringement. Clearly, Bodum thought so. And, Williams-Sonoma’s counsel apparently thought their position to be sufficiently risky enough to justify them settling the case prior to full trial, despite the fact that halting use of the “Bodum” keyword results in a very clear loss of potential ongoing internet traffic and profits.

The reality is that Initial Interest Confusion may continue to be an actionable premise for internet infringement lawsuits for some time to come.