“Black Hat” SEO in Counterfeiting & Trademark Infringement Cases

Sometimes attorneys will focus so much on the clear violations of trademark infringement and counterfeiting of products that they will ignore some of the subtle, hidden aspects of an infringement case. But, if you think about it, a counterfeiter that is selling their fraudulent products online is likely to be working hard to make their website and products appear prominently when consumers are searching for the brand name products on the internet.

Sometimes, counterfeiters do such a good job of online marketing that

Chris Silver Smith

their webpages completely outrank those of the original product creator.

Why do they do Black Hat SEO?

Often, online counterfeiters conduct what is called “Black Hat SEO,” which is a set of organic search marketing methods intended to provide a marketer with unfair advantages in getting their content to outrank everyone else’s in Google’s and Bing’s search engine results pages.

Regular SEO, which is short for “Search Engine Optimization,” seeks to increase the potential that web content will rank higher in search engines (such as Google and Bing) so that the content will be clicked upon and visited by internet users. You may have understood intuitively that ads often appear at the top of search results (called Pay-Per-Click ads, “PPC,” or “Paid Search Advertising”), but in contrast, SEO is a set of practices intended to make pages or other content rank higher in the “organic” or non-paid listings.

The incentive to attempt to outrank other webpages for a valuable keyword is huge, and this is why SEO is conducted.

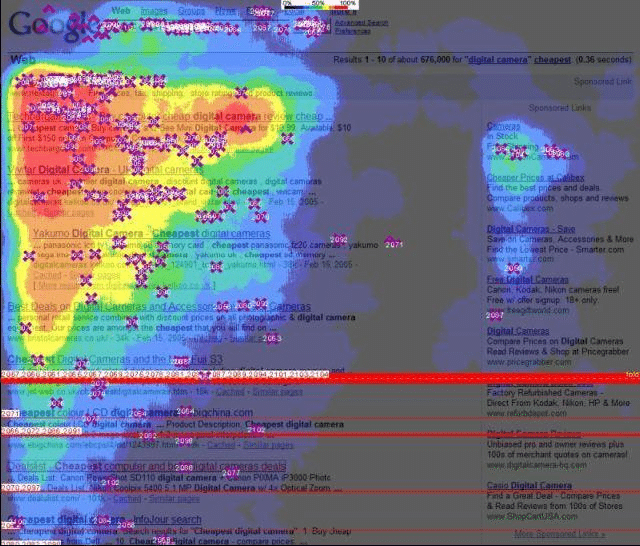

For almost two decades now, industry studies have shown that search engine users look at content the most at the top of the search results pages beginning in the upper left corner and click upon content at the top more than listings found lower on the page. The original Enquiro, EyeTools, and Did-It study used eye-tracking of test subjects and generated a famous “heat map” of Google search results showing what they called a “Golden Triangle” where most people looked as they conducted searches:

Multiple studies have shown that consumers click on listings less as one moves down search engine results pages, with the most clicks generally occurring in the first listing, followed by the next 4 listings, and even fewer clicks as one descends in the results listings. (Sometimes, the last listing on the page gets slightly more attention/clicks than its immediate predecessors.) We used to also state that the listings on the first pages of search results received the vast majority of attention and clicks, as only a small percent of people will click through to the second page of search results, and even fewer past the first two pages. However, in the past few years, Google introduced “infinite” or “continuous” scrolling, which enables one to see more listings past the original ten that were typically on page one.

Thus, to effectively conduct online trademark infringement and sell their imitative wares, counterfeiters will try to rise higher in search results in order for consumers to find them along with the actual brand name company’s assets. In some cases we have worked upon, the trademark owner has been outranked by imposters in searches for their own brand names!

I have worked in two lawsuits where famous fashion trademark owners alleged that another company had infringed upon their marks, trade dress, and patents — and I found evidence indicating black hat SEO had been conducted. I worked on behalf of Versace in Versace v. Fashion Nova as an SEO Expert Witness, and I later worked for Adidas in Adidas v. Fashion Nova.

While I cannot divulge specifics of what I was shown or all my findings in those cases, when I work as an SEO Expert on lawsuits I will cite authoritative sources, such as Google’s Webmaster Central guidelines for SEO, as well as statements made by Googlers in interviews or at conferences, and things they may say in their YouTube channel videos or on social media. Microsoft’s Bing search engineers likewise provide guidelines and statements at conferences, in blog posts, and via social media.

Very amusingly, in these cases, Fashion Nova’s expert, known for writing an SEO book for “less intelligent people,” railed against my clear citations and guidance, trying to falsely claim that Black Hat SEO is no big deal, that “it’s not illegal,” that it’s perfectly fine to use, etcetera ad nauseum. I finally got so disgusted that I pretty much ruined his credibility for court by rebutting his report by quoting his own book back at him, where he described Black Hat SEO as “Dirty Deeds, Done Dirt Cheap,” “tricking search engines,” “dirty tricks,” and “An Arsenal of Dirty Deeds.”

What the expert could not know is that Adidas’ attorneys actually toned down my rebuttal report slightly by extracting additional quotations of his, which they intended to surprise him with during his deposition. These choice quotes I gave them about his Black Hat SEO statements included: “Although search-engine tricks are not illegal per se – at least in the United States, no laws directly outlaw them – it is possible (though quite rare) to get sued by competitors for using such tricks in some circumstances, under unfair-business-practice laws.”

Further, and more dramatically, the expert had titled a subsection of Black Hat tricks in his book “Concrete Shoes, Cyanide, TNT – An Arsenal for Dirty Deeds,” as though he were equating Black Hat SEO to mafia assassination tactics, murderers’ poison, or terrorist attack explosives! I only wish that more opposing expert witnesses could undermine their own testimony so beautifully!

What are some Black Hat SEO tactics?

A number of authoritative sources have defined Black Hat SEO in a number of ways, but what they hold in common is that Black Hat practices contravene search engines’ guidelines, and thus they also contravene their terms and conditions. Black Hat SEO practices are usually efforts to deceive search engines into conveying greater ranking ability than what the content or webpage deserves. They are methods for cheating one’s way up to greater prominence and distribution in search results, and they can also sometimes be intended to trick human search users as well.

Bottom line, everyone’s definitions predominantly agree that Black Hat SEO breaks search engines’ rules.

A Sample of Well-Known Black Hat Tactics:

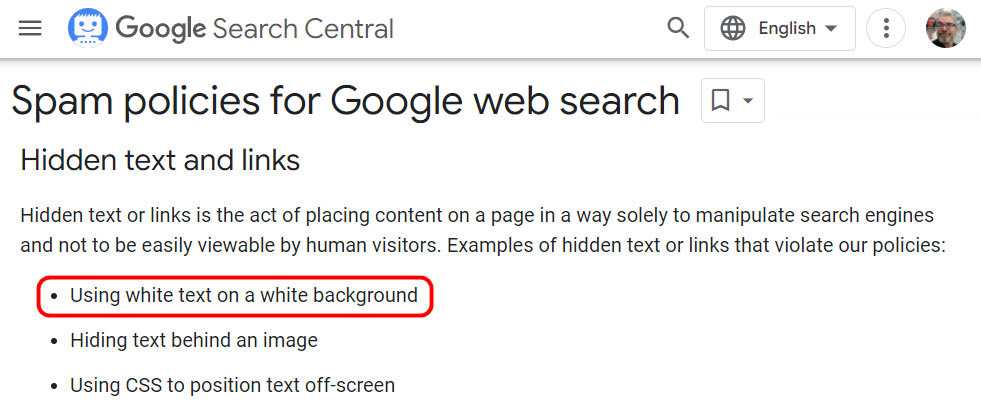

- Hiding keyword text on the page from human users and intending for search engines to use it for ranking purposes. Example: A webpage operated by “Acme Shoe Brand” hides words in their product page by using white text font color on a white background, and the words are multiple Nike brand sneaker varieties. The page is not about Nike shoes, so this is an attempt to appear in search results for Nike’s products in hopes of persuading Nike customers to buy their products.

- Cloaking: a method by which search engines’ bots are shown different content from human users. Example: Showing the search engine a page about erectile dysfunction while showing human users a page promoting Viagra or Levitra.

- Doorway Pages are “…sites or pages created to rank for specific, similar search queries. They lead users to intermediate pages that are not as useful as the final destination.” These are similar in a way to interstitial ads which are shown to users before they can reach their desired content. Google dislikes indexing pages that essentially comprise search results themselves. For example, if Microsoft worked to get Google to index millions of its Bing search results pages for popular keywords, one could search for something like “red shirts” on Google, only to be brought to a “red shirts” search results on Bing. The user wants to click through to a page that has red shirts, possibly for sale, and does not want to click through to find search results where they will have to click yet again to reach what they were seeking.

- Keyword Stuffing is where a webpage has been engineered to contain the same keyword phrase, or multiple similar/related keyword phrases, repeated many times on the webpage to make it appear more densely focused upon the target keyword phrase(s). The keywords can be incorporated as many repeated phrases or nonsensical groupings of words, and often this is combined with hiding unattractive clumps of keywords in invisible text or in extremely tiny font size at the bottoms of pages.

- Targeting a page for irrelevant keywords. For instance, a page could be optimized to appear for searches for “Brittany Spears’ music,” but the contents of the page could all be pornography intended to lure users into clicking affiliate links or paying for subscription services. Notably, creating and optimizing a page to achieve rankings for a competitor’s word mark can be an example of targeting a page for irrelevant keywords if there is no content on the page about the competitor. Thus, a rhetorical “Pepsi” soft drink page should not attempt to rank for “Coca-Cola” searches unless it is using the word, “Coca-Cola,” in a fair use way. For instance, one may conduct “comparative advertising” by showing a page that lists a competitor’s products along with one’s own, showing the similarities, differences, advantages, and disadvantages — using the competitor’s name is okay in such a case, as long as the representations in the comparison are 100% accurate.

- Purchasing Links, Trading Links, and other Link Schemes. Google’s famous, original ranking algorithm was called the “PageRank Algorithm,” and it was based on link analysis. An easy way to explain it is that they have treated links to a page as a sort of vote for that page, and the page with the most votes would rank higher than a page about the same topic with fewer links. The original versions of the algorithm were actually more complex than that, also incorporating the relative importance of each page’s links such that pages with external links from more important/popular pages conveyed a greater value of “vote.” Fast forward to today, and Google’s algorithm and other search engines continue to rely heavily on complex link analysis as part of the linking system. But, it is against Google’s rules to attempt to improve rankings through artificial manipulations, automation, and secret link deals.

- “Googlebombing.” External links can also be used to convey relevance for particular keywords by using “anchor text” with the keywords. “Anchor text” is the text label for a link, and Google and other search engines’ systems may determine that the text describes the page that the link points to. So, instead of a link being labeled “click here,” it could be labeled something like “Gucci handbags,” and the page that the link points to would be considered incrementally more relevant when users search for “Gucci handbags.” This method has been around a very long time, but when it is used to inappropriately convey keyword relevance, it would be considered a Black Hat SEO tactic. Perhaps the most famous example of Googlebombing was when a group of people decided to make former president Bush’s page on the White House website become the highest-ranking webpage when a search for “miserable failure” was conducted, even though the words “miserable” and “failure” were not present on the webpage. Considering how this tactic functions, imagine how a counterfeiter could use this to get their product’s page to rank for a brand name search, and no one would be the wiser as to how the ranking prominence might have occurred. Because this can be a subtle effect, it requires a knowledgeable SEO expert and specialized tools to detect if Googlebombing has been conducted.

Is Black Hat SEO Illegal?

While Black Hat SEO can be limited to just breaking the search engines’ rules, which would not be illegal in of itself necessarily, there are a number of areas where conducting Black Hat SEO is also illegal.

First of all, if Black Hat SEO is focused in whole or in part on deriving benefits through trademark infringement, it is illegal. For example, if one only sells Pepsi products, but one has conducted SEO to rank for Coca-Cola keywords in a non-fair-use manner, then one is attempting to rank for “irrelevant keywords,” which is directly breaking search engine rules.

Some forms of Black Hat SEO involve committing fraud in order to elicit SEO benefits or links.

In yet other instances, Black Hat practitioners have conducted website hacking or have distributed computer viruses in order to covertly insert their webpages’ links into other people’s websites.

In one case I worked upon recently, a financial damages expert strayed out of his lane into opining upon SEO, inaccurately claiming that the defendants had conducted illicit SEO in outranking their website in search results for a contested trademark name. The expert improperly claimed that the number of times the contested name appeared in the website’s HTML code somehow established that Black Hat SEO was conducted. (This is patently untrue, as many parts of a webpage’s HTML code are not at all influential upon search rankings, and the number of times a keyword is mentioned in code is not direct evidence of Black Hat.)

Even more shockingly, the self-styled SEO “expert” falsely claimed that Google’s date search filter allowed him to ascertain historic rankings of webpages, and he used this to further bolster his highly-faulty opinions. It is sometimes difficult to “prove a negative,” such as establishing that a search refinement feature on Google does *not* do something it was never claimed to do. In debunking the ridiculous claim, I asked official search representatives at Google to officially state that it did not work as the opposition expert claimed:

Hey, @JohnMu – I’ve had a preposterous argument with a so-called SEO “expert” who insists that the Date Range search tool shows historic rankings of content, and not just content published within the specified range. Could you confirm it doesn’t represent historic rankings? pic.twitter.com/cuCtWkmlXf

— Chris Silver Smith (@si1very) March 30, 2022

Google’s representatives will not reveal their trade secrets in how their algorithms function, but they often will make an effort to straighten out ignorant, erroneous, and downright false information. In this case, they weighed in and definitively refuted the misinformation:

It does not.

— Danny Sullivan (@dannysullivan) March 31, 2022

You're correct – it's just a filter for the recognized date on a page (which is sometimes hard to get right). The advanced search page ( https://t.co/NH05DOHtiw ) uses the wording "narrow your results by…" for this.

— johnmu is not a chatbot yet 🐀 (@JohnMu) March 30, 2022

Most satisfyingly, I determined that my client’s opposition in the lawsuit had conducted clear-cut Black Hat SEO in developing their own website: The plaintiff had added keyword-stuffed text in white text at the foot of their webpages overlaying a white background. Keyword stuffing and hidden text are provable violations of Google’s rules, and this has been a contravened method for nearly twenty years. Oh, the irony: their expert falsely accused my client of illicit SEO, Google’s own personnel debunked the irresponsible evidence backing up his faulty analysis, and they were conducting demonstrable Black Hat SEO themselves!

Finally, one very rare form of Black Hat SEO is called “Negative SEO,” and it is where a hostile party conducts blatant and illicit link-building aimed at a website in an effort to get the website and its pages to be penalized by Google in search rankings. This can cause the targeted website’s pages to drop lower and out-of-sight in their keyword rankings — this destructive form of sabotage can cost a company its online sales and can allow the hostile party’s competing pages to rank higher as they knock a competitor out of a higher position.

Black Hat SEO can constitute unfair trade practices under the Lanham Act, and evidence establishing that it has been done can further clarify for judges and juries where a party has cheated in order to gain undeserved advantage in the online marketplace.

How Determination of Black Hat SEO Helps in Infringement Cases

If Black Hat SEO is detected, there are a few ways that it can help a plaintiff in a trademark infringement complaint.

First, there are a number of hallmarks that can indicate that a Black Hat SEO campaign has been conducted intentionally, and showing deliberate/willful intention to infringe can allow a victim to be awarded up to three times their actual damages.

Second, if your client’s lawsuit involves trademark infringement with any sort of online component, there may be more elements involved with infringement that can only be detected by someone skilled at SEO. Detecting hidden infringement in a case can help further drive home that something untoward was done and can expand elements in determining damage exposure. If illicit SEO was involved, then the number of times webpages, images, or videos were seen in search results may provide additional bases for expanding the number of times an infringing mark could have been seen by consumers.

Third, even if infringement was unintentional, the incorporation of a word mark could expand exposure by making a webpage more relevant in search engines’ algorithms — the search optimization may not be intentional, but an expert who understands how search rankings are affected can help establish and measure how many misimpressions content involved with a mark may have accrued.

Fourth, while improper use of a trademark on a webpage provides an obvious instance of infringement if Black Hat SEO has been conducted, the infringing mark could be displayed to consumers within search engines’ search results, depending on how the optimizations were conducted. In PODS v. U-Haul, the use of PODS’ name in uhaul.com’s HTML title tags and meta description tags magnified the misimpressions by a number of times, increasing the basis for damages considerably.

Finally, those skilled in SEO can often provide evidence indicating that some levels of confusion have occurred among consumers when search marketing data shows that two-word marks have been combined or confused when numbers of users have conducted searches. Searches like “are Brand X and Brand Y the same” or “is Brand X the original” provide implicit intent and show real consumer confusion. If one brand’s analytics data shows search referrals from people searching for the other brand’s word mark, and those searchers clicked through to the wrong website, it can establish both confusion as well as potentially inappropriate keyword rankings.

Awareness of potential SEO involvement can make a difference in winning infringement cases, and in the size of damages awards. The tech-savvy attorney that makes an effort to understand how SEO may be involved in cases with online infringement components is certain to provide a clear advantage to their clients.